I recently had the opportunity of leading a workshop at the Royal Netherlands Institute of South East Asian and Caribbean Studies in Leiden, the Netherlands, on the 8th and 9th of September 2016 with the goal of bringing scholars together and teach them how to apply a number of basic digital tools on a dataset of military memoires. I tried to optimize the learning outcomes by carefully tailoring the content of the presentations and assignments to the level of understanding of the participants. As the feedback from the group was quite positive, I would like to share some of my findings.1

If I can understand what is presented during the workshop, then anybody can!

Are you familiar with the experience of enrolling in a workshop on Digital Humanities with the intent to enhance your academic skills, only to find yourself completely lost due to the combination of new terminology, unknown graphic interface, unfamiliar data, outdated version of a program on your computer and limited time to ask questions and complete assignments?

I have no problem admitting that this has happened to me over and over again. Teaching me the mathematical principles upon which information technology is built requires a great deal of patience and pedagogical skills from an instructor. But the cumbersome process eventually pays off: once I have understood how digital tools work, I am the perfect ambassador for promoting and designing environments in which the principles of Digital Humanities are tailored to the level of understanding of digital novices. This is a first but necessary step to be able to eventually incorporate digital tools into standard academic practices of research and teaching further down the line.

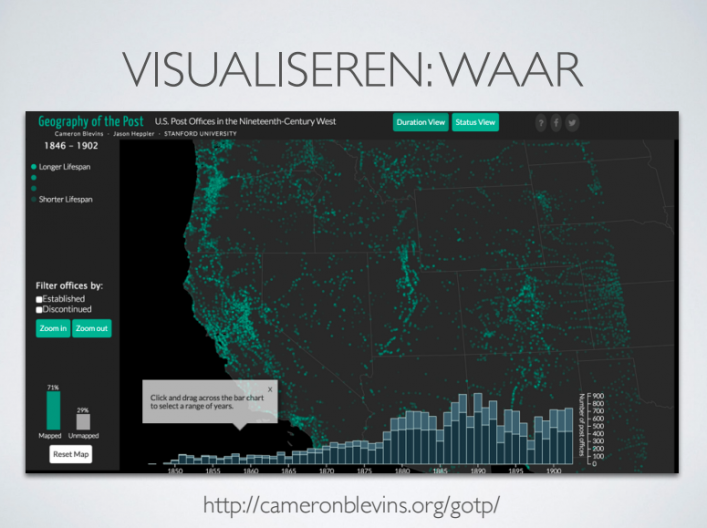

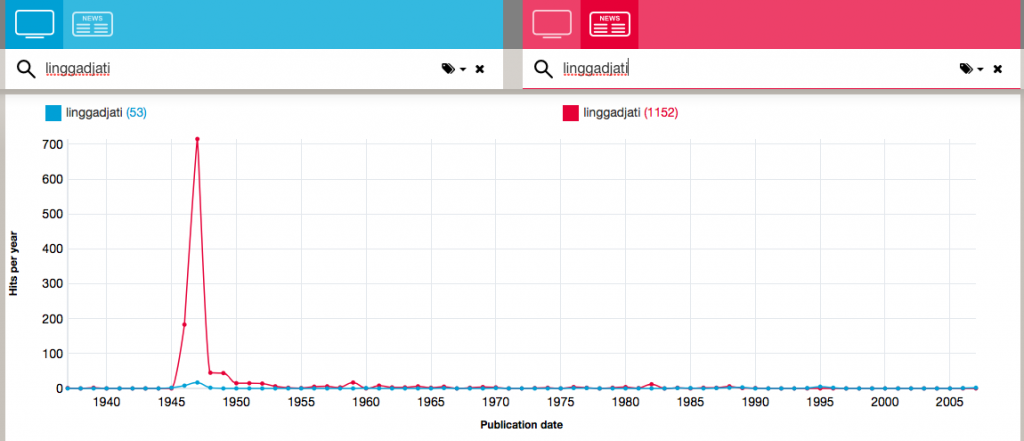

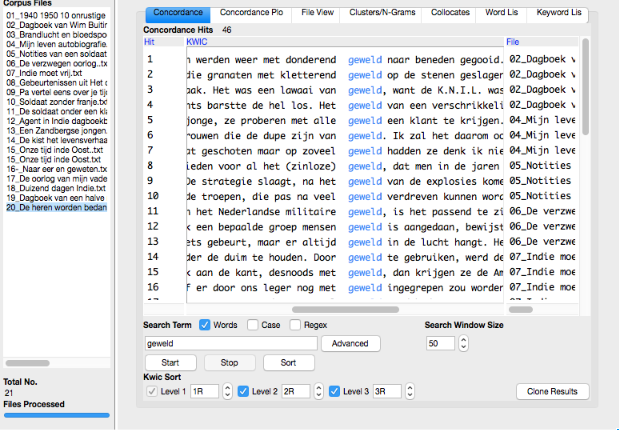

The instructors were invited to present an introduction and create a number of assignments on the following topics: visualisations, linked data, text mining and crowdsourcing.

They were all asked to commit themselves to a scenario designed by me that followed a very basic logic: defining the purpose of the application, showing a variety of best practices and addressing misunderstandings that are recurrent. Both presentations and assignments were meticulously cleared from jargon, abbreviates and implicit wordings in a continuing conversation between me and the instructors, using e-mail, skype and face-to-face meetings. This required a certain amount of flexibility on their side, as they had to endure my interference with their expertise and teaching habits. With regard to the assignments, the instructors were encouraged to use screen shots to illustrate the smallest possible next step in the assignment. They had also been provided with the results of a survey that had been sent to all participants in advance, with the request to describe their associations and experiences with the selected four topics. The instructors were also asked to specifically refer to this feedback during their presentation, to enhance the feeling among participants that their effort of completing the survey was reflected in the way the instructors handled their questions and concerns.

Choosing data that connects to the domain expertise of the participants supports the learning process and stimulates creativity, collaboration and an understanding of the added value of sharing data

There is a limit to the amount of disruption of engrained academic practices and reflexes that researchers can handle at any given time. If a workshop of consecutive days introduces 3 or 4 different tools, each with a different type of data that does not belong to the domain expertise of the participants, with explanations varying in levels of complexity, there is a high risk of participants loosing focus and backing off. To minimize this risk, it is useful to integrate a number of elements in the structure of the workshop that are similar. These can be the logic or order of the explanation or the design of the workflow to get tools and data ready for the assignment. Of foremost importance is the choice of the data and their integration into the different applications that are discussed. If feasible, it is recommended to select data that strongly connects to the expertise of the participants and that features as a recurrent theme in de different applications that are discussed.

This way participants are provided with a sense of continuity. In our case, the database with military memoires was used to show examples and complete assignments in all the four subsequent Digital Methods that were discussed. This approach assumes that operating within this ‘comfort zone’ will lower the threshold for understanding how the tool processes the information. This does, however, have consequences for opening up the workshop to anyone with interest. In this case, a deliberate choice was made to first invite a mix of scholars and cultural heritage experts that had one thing in common: an interest in the Indonesian war of independence between ‘45 and ’49. We also reserved some places for other participants with no specific ties to this topic.

This topic-oriented focus had an additional purpose, namely to bring together ‘knowledge’ brokers around the subject of Dutch violence in Indonesia, in an ‘hands on’ environment. There are already existing initiatives to fuse efforts at the institutional level but the focus is mainly on securing resources for additional research positions. What still needs to be developed, is the principle of moving from ‘me and my publication’, to ‘our collaborative project’.

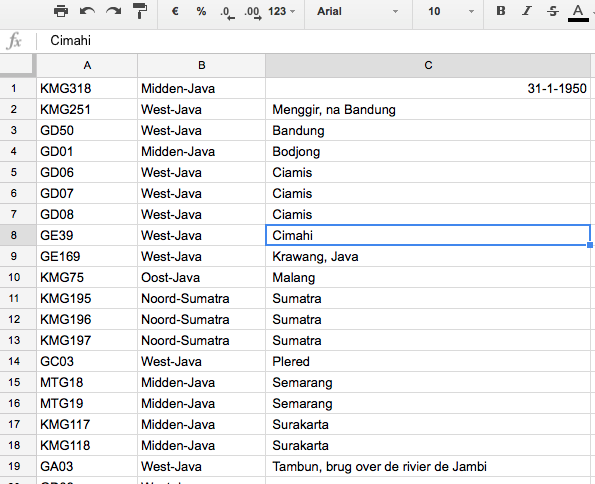

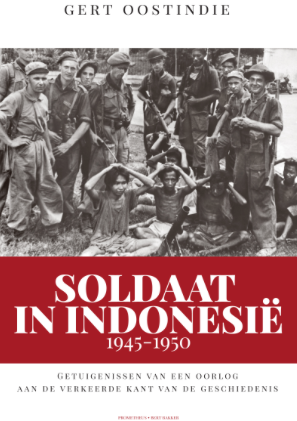

A prerequisite for such an approach is the availability of a rich and relatively under-exploited dataset on the topic of the war in Indonesia between 1945 and 1949. The group was fortunate to have such a resource, as the KITLV offered to share its database with metadata on 700 military memoires with the workshop’s participants. It was a case of re-use of data in digital form, as that particular information had already provided the backbone for the analysis of the memoires published in Soldaat in Indonesie, by Gert Oostindie, the director of the KITLV.

A provision had to be made, however, to secure infractions of privacy law and copyright restrictions. The participants were all asked to sign a document that stated that the data that had been downloaded on their computer, or placed in a collaborative online environment, was not to be spread or used for other purposes than the workshop without prior consent of the KITLV. Eventually the dataset will become available to the public. A feature to stimulate future collaboration was to select a number of open calls for research pilots and workshops and present them at the end of the workshop as opportunities for a follow up.

Selecting a topic which is societally salient and relatively under- researched contributes to enhance cross-institutional and cross-disciplinary collaboration.

The dataset that was made available addresses a controversial topic with strong impact in every possible realm of society: The traumatic memory of the Dutch-Indonesian decolonisation war waged between 1945 and 1949. This conflict has left its traces in minutes of government, headlines of newspapers, current affairs programs, military cemeteries, mental health institutions, museum depots and family memories.

The character of these traces however, are in stark contrast with those left by the previous ‘good war’ (1939-1945), when fighting the German enemy eventually led to victory. Indonesia, not only defeated the Dutch, but by reverting to guerrilla warfare tactics for lack of resources and weapons, induced the Dutch enemy to deploy a policy of counter-guerrilla. This led to the occurrence of war crimes on a considerable scale. The war caused the estimated death of some 150.000 Indonesians and 4000 Dutch military. It also had a long term effect, as 5 to 7 % of the deployed Dutch 170.000 military suffered from PTSS. Data on similar effects on the Indonesian side are unknown. As reputations of Dutch authorities were at stake, as well as the interests of companies wanting to continue their business in Indonesia after 1949, the subject of Dutch war crimes remained a taboo for several decades. This, strangely enough, applied also to Indonesian authorities, who preferred not to address the equally harsh methods that had been imposed on their own people by guerrilla freedom fighters to enforce loyalty to the cause of independence.

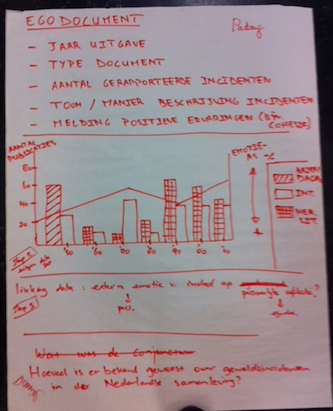

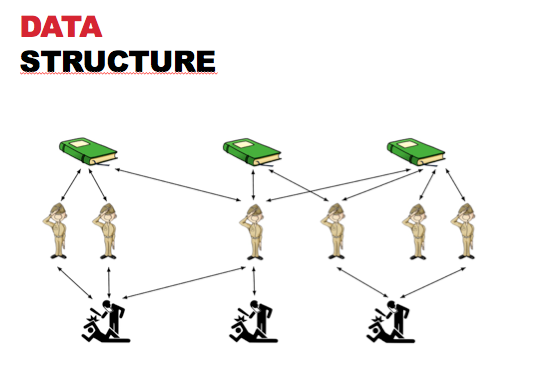

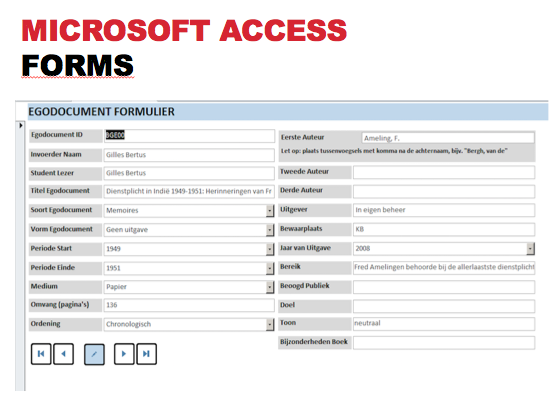

The frequency and scale of Dutch violence and the political and moral responsibility for them have remained a hotly debated issue in the public realm. At the same time there was an lack of interest from the side of the academic community, until the recent victory of the human rights specialist Liesbeth Zegveld in 2011. She won a law suit against the Dutch state, compelling it to offer apologies and compensation to the Indonesian survivors of one particular case of mass murder. The topic of Dutch violence was finally placed on the research agenda of the most influential research institutes: the KITLV, NIOD and NIMH. The director of the KITVL, Gert Oostindie created a de facto crowdsourcing community, led by coordinator Ireen Hoogenboom, consisting of a large group of student apprentices who during subsequent years systematically read and annotated 700 memoires of military men. A relational database, created by the sociologist Daniel Blocq, tied variables of a given publication with variables of its author and variables of the incidents of violence mentioned in the publications. The collection consists of a mix of 700 documents: contemporary diaries, collections of letters, as well as retrospective accounts varying from the history of military units to very personal reminiscences. These had been published in previous years by veterans from different branches of the Armed Forces.

The context of the workshop offered information scientists, archivists, librarians, documentary makers, historians, linguists, anthropologists, Indonesian language specialists, museum curators and a veteran service institute the opportunity to share their expertise.

Learning and discussing a complex new skill is best done in one’s native tongue

Computer scientists have the tendency to forget that novices to Digital Humanities have to learn a new language when they venture into Information technology. Even when explaining the simplest step, such as switching from one tab to another, requires a notion of what a ‘tab’ is, and an understanding of the fact that it remains directly accessible, while not visible.

What adds to this complexity is that various disciplines use different terminology for similar practices or the same terms for quite distinct practices. An anthropologist analyzing transcripts will refer to ‘coding’ his or her data, while a computer scientist uses this term refers to using programming language to create tasks that the computer can perform. There is often confusion about the exact meaning of the terms ‘metadata’ and ‘annotation’, depending on whether the reference is to an activity performed during the creation of an archive or the analysis of a document as an individual research activity. Then there is the visual component, the capacity to think of a single screen as a menu, that can bring you to other virtual places, with a whole range of choices. Then there is also the fact that you can switch from stand alone to online, and from front end to back end of your computer, when you install a programming language.

To be able to explain basic and more complex principles, clear up misunderstandings and offer useful analogies, it is necessary for both sender and receiver of information to express oneself in nuances and fully master a language. Though this speaks for itself, most DH workshops even outside Anglo-Saxon communities are held in English. This is because most available tools are in English, and the DH community consists of a melting pot of scholars from all corners of the world.

Notwithstanding the great advantages of this globally oriented DH community with English as a lingua franca, when it comes to introducing novices it should seriously be considered to opt for the native local language during the workshop . It not only makes it easier to address complex problems, but is in line with the character of the data which is in the local language. Finally, it lowers the threshold for participants coming from a non- academic environment.

For DH to really become a shared resource that can enrich both academia, the cultural heritage field and the growing community of citizen scientists who are waiting to get involved, it is of utmost importance to develop DH material and resources in the local language.