The topic of my presentation was not linked to any current project, and it was partly based on my past research on the history of cultural policy in Luxembourg. The idea to organise a panel on the uses of the past occurred to me in 2019, partly because this topic was present in my research, but also because I felt that it was very up to date. Three colleagues and I submitted the panel proposal. As the conference did not take place as planned in 2020, we resubmitted our panel proposal for the 2022 conference.

In the final panel in August 2022, two colleagues who were part of the original proposal could unfortunately not participate. Nevertheless, I was delighted that it could take place after three years of coordination, including very insightful presentations by the other two panellists, Vera Dubina and Sylvia Bailey. Serge Noiret chaired the panel.

In my presentation, I talked about the political use of history by the Luxembourg government in recent decades and focused on two dimensions of this use. The introduction briefly reflected on the concept of “political use of history” and discussed the uses of the past identified by Klas Göran-Karlsson.1

Protecting a “national identity”

I began with the 1980s as this period marked a turn in the government's attention to history and memory politics. The audiovisual memory campaign aiming to collect photographic material about the industrial south of Luxembourg is one example. The protection of a national identity (or cultural identity) became a policy objective of the government. Of course, the question of national identity was already present in public and political discourse in the preceding decades. However, it was a concern that explicitly appeared in official policy documents at the end of the 1980s. The attention that the government paid to national identity might be explained by at least a couple of reasons: the appearance of nationalist, right-wing movements in the 1980s – to which the government attempted to react – and the European integration process (Treaty of Maastricht in 1992), triggering fears that Luxembourg might lose its identity in a Europe of open borders. In 1991, the Ministry of Cultural Affairs was explicit in this respect, highlighting the need to strengthen “our cultural identity” and to develop initiatives that promote “our cultural heritage” in view of 1993 (creation of the EU common market).2

In this context, Luxembourg celebrated the 150th anniversary of its independence in 1989. The government commissioned a national exhibition, De l’Etat à la Nation, coordinated by the late historian Gilbert Trausch. The goal consisted in showing the development of national consciousness.

The exhibition catalogue disseminated tropes of the master narrative (in an updated version including the Nazi occupation). It reproduced, for instance, the idea of a massive resistance during the occupation, while completely ignoring collaboration. The exhibition was an example of a public history initiative linked to the idea of protecting and promoting national identity.

- 1. Karlsson Klas-Göran, ‘The Uses of History and the Third Wave of Europeanisation’, in A European Memory? Contested Histories and Politics of Remembrance, ed. Malgorzata Pakier and Bo Strath, Studies in Contemporary European History 6 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2010), 38–55.

- 2.

Ministère des Affaires culturelles, Rapport d’activité 1990 (Luxembourg: Ministère des Affaires culturelles, 1991), 6.

During the 1990s, another objective was added to the protection of national identity and became explicit: the improvement of Luxembourg’s image. This second objective has possibly superseded the first one over time, without ever replacing it.

Defending Luxembourg

Only a couple of years after the national exhibition of 1989, the Luxembourg government organised a travelling exhibition entitled Imago Luxemburgi. It was supposed to tour all European capitals until 1995, the year in which Luxembourg City was the European Capital of Culture. Though I could not yet determine if it was indeed shown in all the capitals, it was hosted at least in Amsterdam and Prague.

This exhibition was an example of the new political concern to promote the country. For the Luxembourg government, such an exhibition would be appropriate at a time when Luxembourg should “defend” its place at the international level and improve its image. The exhibition should show that Luxembourg is not just a small country with a lot of banks, as the following quote – from 1989 – shows:

At a time when Luxembourg has to defend its place at the international level, it seems timely and urgent to set up a mobile exhibition on Luxembourg. The lack of knowledge about Luxembourg is indeed frightening and requires a vigorous reaction from the Luxembourg authorities if we want to prevent the image of Luxembourg from remaining that of a small country with many banking institutions.1

Despite the exhibition catalogue stressing that it does not impose an “official” image of Luxembourg, this was still the case. Exhibitions are never innocuous and conceived in a neutral space, disconnected from their context. They are based on choices that actors deliberately make, even if these choices might not be transparent to the visitors.

The travelling exhibition aimed to depict Luxembourg as an “anticipation of tomorrow’s Europe” (“préfiguration de l’Europe de demain”) and with its own cultural identity, more complex than a “banking paradise”. According to the foreword by the then prime minister Jacques Santer:

This exhibition aims consequently at presenting a modern European country with a history and a cultural identity of its own. This genuine Luxembourg “civilization” has always been characterized by a real European dimension, by its capacity to assimilate foreign influences and to articulate a synthesis of the Roman and Germanic cultures.

The exhibition was possibly the first initiative in the 1990s to use history for promoting Luxembourg’s image abroad. The exhibition, as well as other initiatives since the 1990s, was pervaded by a kind of tension between exhibiting a national identity – which was never clearly defined – and showing the openness of a country and its European dimension. The European Capital of Culture in 1995 is one notable example of the 1990s, when the main theme was the “dialogue” of cultures, depicting Luxembourg as a crossroads of cultures.

Branding the nation

In 2014, a further step was taken with a nation-branding campaign to attract tourists, companies, and investors. A marketing agency was commissioned by the government to develop a country profile.

In nation branding, history also plays a role. The official website includes a section on Luxembourg’s history, but the articles lack a critical approach. For instance, one article is entitled “400 years of foreign sovereigns”.2 This trope was already used a century ago in the master narrative, based on the idea that after the Middle Ages, Luxembourg was not independent anymore. However, one cannot speak of foreign sovereigns for a period when ruling structures, borders and states bore a different meaning or worked differently than today. Furthermore, a Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg did not exist at the time.

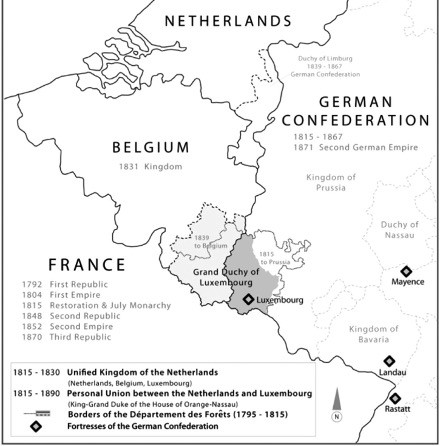

In 2019, a booklet was published by the government on the history of the country.3 It was written by Guy Thewes, the director of the Luxembourg City Museum. Tellingly, the booklet dedicates a page to the “myth of foreign domination”, thus contradicting the narrative as suggested by the title of the article on the webpage mentioned above. However, it comes with its own set of issues. It uses, for example, a wrong map of the territories ceded by the Duchy/Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg in the 17th and 19th centuries, lacking historical depth. This map has been used for decades in schoolbooks and was reproduced in the catalogue of the 1989 exhibition. The borders of the territories ceded to France, Prussia and Belgium are incorrect. The fact that “Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg” is inscribed on the map suggests a continuity that did not exist.

- 1. Translated from French. "A un moment où le Luxembourg doit défendre sa place au niveau international, il paraît opportun et urgent de mettre sur pied une exposition mobile sur le Luxembourg. Le déficit de connaissances sur le Luxembourg est en effet effarant et demande une réaction vigoureuse de la part des autorités luxembourgeoises si on veut empêcher que l’image du Luxembourg ne reste celle d’un petit pays d’opérette doté de nombreux instituts bancaires." ( Ministère des Affaires culturelles, Rapport d’activité 1989 (Luxembourg: Ministère des Affaires culturelles, 1990), 12).

- 2. https://luxembourg.public.lu/en/society-and-culture/history/400-ans-occu... (last access: 19.09.2022).

- 3. The booklet can be downloaded here: https://luxembourg.public.lu/en/publications/ap-histoire.html (last access: 19.09.2022).

In the section on the Second World War, the booklet presents the high moments of resistance, while only briefly mentioning the question of collaboration in half a sentence (“While collaboration was not unheard of during the occupation, the majority of the population nevertheless bore witness to a remarkable national cohesion.”, p. 18).

The publication elicited criticisms from historians. The historian Vincent Artuso, who researched collaboration during Nazi occupation, intervened on the public radio 100,7. He called the booklet a “state-promoted feel-good history” (“staatlech favoriséiert feel-good History”) used to improve the brand Luxembourg.1

Final thoughts

I wanted to analyse the use of history in Luxembourg as an example of a liberal democracy. The uses of history may vary depending on the regime type. More importantly, though, I wanted to raise some questions for possible further debate:

- The tension (or not?) between disseminated, officialised narratives vs. critical historical research of historians;

- the role of historians and how critical historical research can be included in state-commissioned exhibitions, booklets, etc.;

- how should historians react publicly to state-commissioned initiatives, including old tropes of the master narrative?

In my opinion, historians have a responsibility to criticise the political use of history and to promote a critical perspective on our past. However, this is easier to do in democracies than in authoritarian regimes.

- 1. https://www.100komma7.lu/program/episode/186810/201801180940-201801180950 (last access: 19.09.2022).