The exhibition La Forge d’une société moderne (Centre national de l’audiovisual, 10 June–17 December 2017) is the result of two research projects entitled “Fabricating Modern Societies” (FAMOSO), funded by the Fonds National de la Recherche in Luxembourg. A team of seven researchers has been working on the different strands of the projects for the last four years. The overarching theme is the question of how modern technologies and approaches that were employed to optimise the human body and social fabric in the era of industrialisation shaped modern Luxembourg. The starting point for FAMOSO was a holding of more than 2,400 glass plates discovered in an abandoned storage room in 2007 at the Institut Emile Metz, once one of the most progressive professional schools in Europe, established by the Luxembourg steel-manufacturing conglomerate Aciéries réunies de Burbach-Eich-Dudelange (ARBED) in 1914. The assemblage of glass plates initially functioned as a working archive for ARBED. Many images depict the company’s social and educational initiatives, its products and workers, and the achievements of industrialisation and scientific progress in Luxembourg. Over a period of ten years the glass plates were restored, digitised, catalogued and archived in the HISACS Institut Emile Metz collection at the Centre national de l’audivisuel in Luxembourg, before being analysed for the FAMOSO projects at the University of Luxembourg. The FAMOSO projects also include a public history project, the exhibition La Forge d’une société moderne. This exhibition was designed and organised in cooperation with the Centre national de l’audiovisuel, thereby establishing a connection between archives, researchers and a museum, between the Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C2DH) and the Centre national de l’audiovisuel.

In this essay, I would like to reflect upon what happens when archival material and research are transferred into the three-dimensional physical space of a museum. A main focus will be on what happens when restored, digitised and partly retouched glass plates are framed and staged in a museum setting.

Showcasing histories in the physical space of a museum means choosing a specific take on historical events and archival materials. It means showing and showcasing the past in a specific way and indicating how histories could or should be seen or looked at.

Showcasing objects and histories involves two basic professional operations performed by curators: selecting and arranging. Selecting implies developing a convincing research-based thematic scope, drawing on a huge variety of archival material and the different thematic options offered by an archival collection. In the case of La Forge d’une société moderne, the curators, one of them a member of the FAMOSO research team, decided to focus on how photography was used as a technological and communications tool to promote cooperate identity and shape modern Luxembourg. At a time when Luxembourg’s industrialists were eager to become a progress-oriented elite and to assume a leading role in shaping the societal fabric of modern Luxembourg, images reproduced in promotional brochures, pamphlets and magazines (and in a promotional film) not only reached out to business partners but also came into action as social, cultural and political agents when responding to Catholic conservative circles and a number of socialist and communist workers’ associations.

After selecting and shaping the thematic scope of an exhibition, curators have the task of carefully arranging the objects in space. They do not only rely on the immediate visual appeal (Schauwert) of objects; they also develop certain display strategies as a means of storytelling by arranging these objects as agents of interactive play. Indeed, curators put objects on stage; they carefully arrange a dramatic ensemble to construct a story designed to trigger the viewers’ imaginations and to facilitate a specific perception of history and involvement with the past.

Arranging objects as a means of storytelling is a creative act – it is the creation of a performance that is aimed at and reaches out to the public. The arrangement of objects and related display strategies are a form of aestheticisation.

The concept of aestheticisation has different levels – sometimes the transformation is referred to within the exhibition itself, but in many cases viewers are not aware of the “tools” hidden in the black box of curating. Aestheticisation ennobles the objects on display, even if, as is the case in La Forge d’une société moderne, these objects were once part of the everyday practice of promoting a specific image of a company. As circulating media they of course had strong effects on the shaping of society, but they certainly never belonged to the sphere of fine arts or high culture in Luxembourg. This implies that objects change their meaning and value once they enter an archive and the space of a museum; they change their status, become objects of national heritage and are aestheticised by specific modes of display. The white gloves of archivists and curators when handling historical objects testify to this in a symbolic way.

For La Forge d’une société moderne, some digitised glass plates were reproduced using present-day techniques and put into frames, while other reproductions were displayed in light boxes or in a slide show. They are juxtaposed with their historical reproductions in printed form, with some arranged in display cases and others displayed in enlarged formats on panels with captions added to them. The original glass plates are not exhibited in La Forge d’une société moderne, but the curators added a vitrine that provided information on the restoration and archiving process. The decision to exclude the original glass plates was taken because of their fragility and the damage that would be done by exposing them to light. As no original photographic copies existed, the curators examined the various options and finally decided to showcase the vast majority of the images selected for the exhibition as high-quality ink prints of digital copies of the glass plates. In most cases, the images were selected based on criteria related to artistic or photographic value and evidence of reproduction. Many images shown in La Forge d’une société moderne were carefully retouched before printing in order to achieve the best possible result using present-day technologies. The historical images therefore assume a “curated” or aestheticised materiality of the present time, moving them closer to the sphere of artistic photography. This transformation, based on new digital retouching and print technologies, was emphasised by the decision to display them in exquisite, carefully chosen wooden frames arranged tastefully on the walls of the museum.

Indeed, within the exhibition the materiality and meaning of the glass plates was transformed and ennobled by aesthetic means and related display strategies. This is not necessarily a disadvantage as the presentation and arrangement of objects in the museum space actually make us see and perceive objects in new ways. Viewers are encouraged to imagine a specific version of the past. This guided perception is facilitated by the artificial space of the museum that does not explicitly represent historical reality but instead offers a selection of perspectives, an interpretation, a specific means of storytelling and a carefully designed performance of the past using display strategies in a three-dimensional space. On the negative side this also implies that curators follow certain unspoken norms of display and, as such, change the meaning of things without discussing this transformation with their audiences.

La Forge d’une société moderne as an arrangement in a physical space indeed appeals to the human senses and, as such, makes its audience experience in real space and time the layered and complex networks of the HISACS collection. The appealing quality of the exhibition makes visitors come closer and get involved in or become part of these networks – physically with their senses, intellectually, and emotionally.

This involvement in a network of images in many cases triggered memories among the audience. Some visitors approached me to confirm that the message portrayed by the exhibition was an accurate reflection of their own experiences and memories. Others explicitly wanted to become involved. I saw this as a sign of the social power of photography and exhibition design to reach out to audiences and draw viewers into existing networks of meaning-making. The urge to get involved encouraged some visitors to contribute to the “story” of the exhibition with objects from their own personal “archives”, keen to let these materials participate as new actors within a complex web of history and meaning-making.

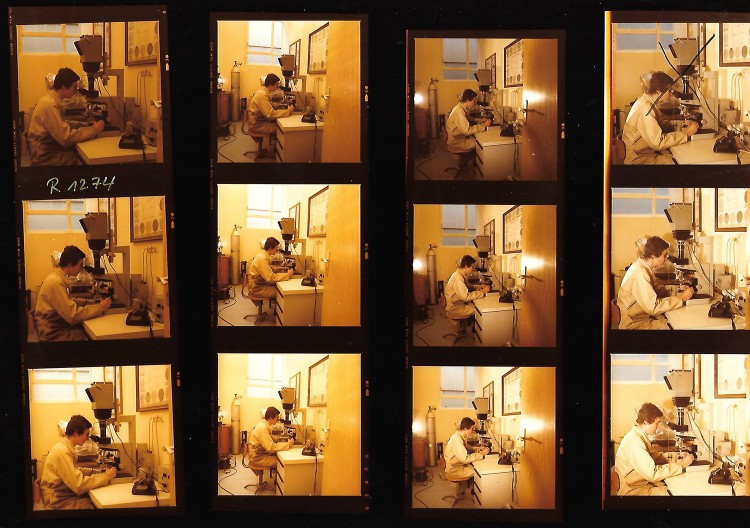

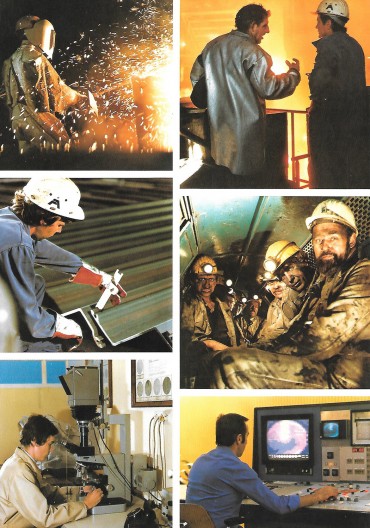

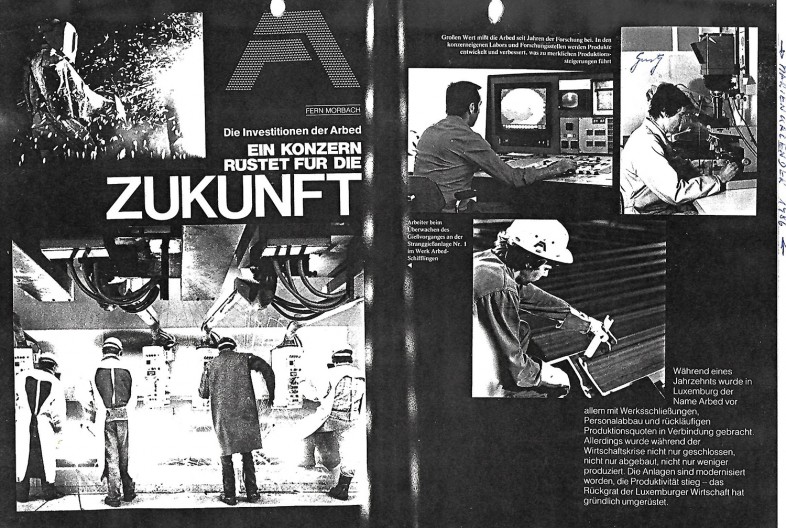

After the opening of the exhibition, a former employee of ARBED sent me a few selected digital copies of his own personal collection. He told me that he received his professional education at the Institut Emile Metz in Dommeldange. After his graduation in 1974 he worked for many years in a research laboratory for a sub-company of ARBED. The files he sent me include one contact sheet with twelve images taken with a middle format camera (fig. 1). A second document indicates that these images were produced by the ARBED Photographic Department. The images show a young man working in a laboratory. One of the images was chosen for reproduction in ARBED promotional brochures (figs. 2, 3 and 4). This of course confirms the message of the exhibition La Forge d’une société moderne. According to additional information that arrived in an email with the files, the photographs were not staged; they were taken without permission as the ARBED photographer did his job by just walking through offices, laboratories and production sites while observing through the lens of the camera. It appears that in the 1970s, much more so than before, ARBED favoured a style of image production that came very close to documentary photography. In addition, the email informed me that in 1979 its sender personally witnessed that approximately 90% of the photography archive at ARBED Dommeldange had been destroyed. This information confirms the existence of gaps in the archives, a situation which also affected research done during the FAMOSO projects. In addition, this testifies to the basic tensions that exist between preservation of the past and the force of progress. The fact that objects are exposed to destruction shows how the same objects can be perceived as everyday items and treated as superfluous clutter at a certain time, whereas in another era they can become objects for the preservation of a meaningful past.

Although ARBED’s own archives have been largely destroyed, many former employees of ARBED have saved materials by establishing “private” and very personal collections, and it is important to use these materials to continue to diversify the fascinating story of La Forge d’une société moderne; plans are already afoot to do this via a digital database. This database will not only extend the collection of objects and texts but also help tell the diverse and multiple stories of Luxembourg’s industrial past.

In conclusion, I would like to stress that a virtual exhibition or a digital database cannot replace the sensory power and specifically selected story presented in a physical exhibition space – quite the contrary. I think that both the physical and virtual spaces of presenting and showcasing history are important: they reinforce each other, creating synergies and thereby serving different purposes.