This cultural event gives us an opportunity to present the situation of the Jewish community during the “normalisation” period, which was undeniably unique in terms of its microcosm. Since spring 2017, visitors to the Jewish Museum in Prague have been able to visit a unique exhibition in the Robert Guttmann Gallery. The exhibition presents specific cases of State Security (StB) operations against Jewish communities, the dilemmas faced by community members, and the involvement of several members in dissident and other activities outside the official scope of Jewish communities. For our research, it is interesting to see audiovisual propaganda against the European Zionist movements captured on several newly accessible recordings.

Yet the exhibition shows more than the myriad forms of “anti-Zionist” propaganda: “normalisation” also entailed the destruction of Jewish cemeteries, the demolition of synagogues, the obstruction of research into the fate of Jews during the Second World War as well as policies that nearly eradicated Judaism completely. Visitors can also familiarise themselves with newly discovered photos of members of the Czechoslovak Jewish community in the late 1960s and 1970s. Moreover, I appreciated the atmosphere of the entire exhibition, which, while somewhat “gloomy”, is also extremely impressive. Visitors are taken through a black labyrinth, where they can see the exhibits displayed on black walls accompanied by explanatory texts. In my opinion, the exhibition is well organised and very instructive even for visitors with no previous knowledge of the subject. The majority of the documents and photographs are being exhibited for the very first time, and the historical background is clearly described.

Czechoslovak normalisation from the perspective of propaganda documentaries

The period after the Warsaw Pact forces invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968 was referred to as “normalisation” by communist ideologues. Under the watchful eye of the Soviet military occupation, Czechoslovak society was to return to “normal”, in other words to a rigid ideological socialism with a single political force having an unchallenged monopoly of power and wholly subject to Moscow’s dictates.

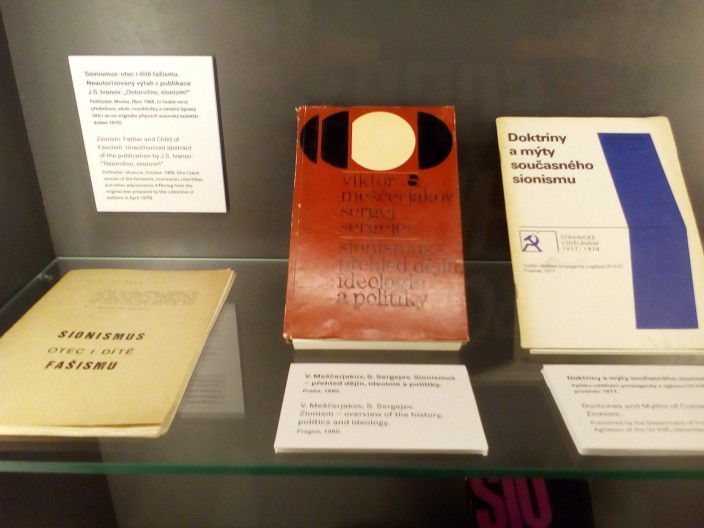

The Kremlin considered anyone with Jewish ancestry or who even stood by the Jews to be a Zionist. Many Czechoslovak communists adopted this definition, and after an interval of many years, the State Security began to compile lists of names of those with Jewish heritage for “operational usage” in the fight against Zionism. For anyone interested in examples of audiovisual propaganda, there are a few revealing recordings from Czechoslovak television in 1982. I was also fascinated by the unauthorised abstract of the publication by J. S. Ivanov, “Ostoržno, sionism”, published by a collective of authors in 1970.

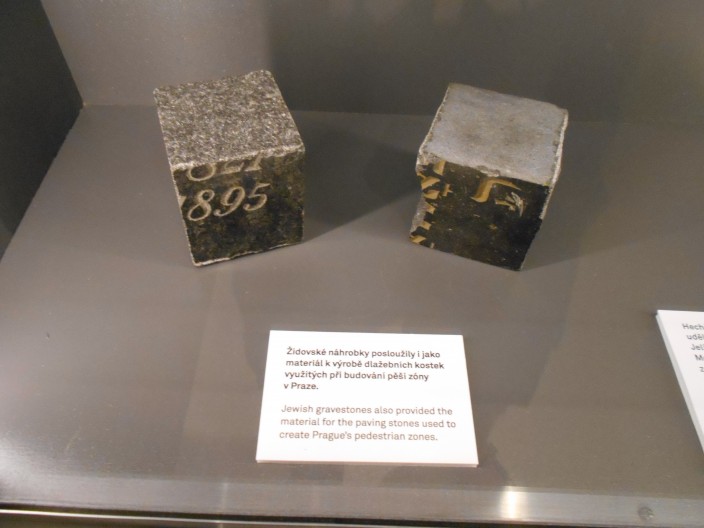

The exhibition once again opens up the question of the mass theft of lucrative granite headstones. Whole cemeteries were sold to private buyers and the police intervened more than once on seeing trucks and cranes removing dozens of headstones through demolished cemetery walls. A large number of these granites tombstones were used to pave the pedestrian areas in the centre of Prague. The entire exhibition shows the efforts made to preserve Czechoslovak Jewish traditions despite the coordinated attempts of the communist regime to suppress any sort of meaningful activity.