As part of the research project “Remixing Industrial Pasts in the Digital Age”, a Temporary History Lab was set up in the Annexe22 pavilion on Place de la Résistance (Brillplaz) in Esch-sur-Alzette. The aim of the programme was to reduce the distance between the research team of historians and anthropologists and the people whose stories they are investigating. The following review reflects on the process and difficulties of this first milestone of the project. The COVID-19 pandemic proved to be a hurdle in many respects as well as an opportunity to break new ground.

Historical scholarship is usually taught as the gathering and processing of historical knowledge from archives, libraries and digital resources. Even contemporary historians tend to keep their distance from their research subjects, human beings, instead remaining in their academic “ivory tower” and preferring to encounter them indirectly through the intermediary of sources and literature. When oral history interviews are conducted, the distribution of roles between the questioning historian and the responding contemporary witness is clarified in advance and the interview situation is organised. Historians and anthropologists learn and practise appropriate scholarly methods for such interviews, especially how to deal with proximity to and distance from the interviewed contemporary witness. By its own definition, public history tries in various ways to reduce the distance between academically trained historians and their research “subjects”, to create proximity and to investigate history together through direct (face-to-face) exchanges such as history workshops.

Work in the Temporary History Lab

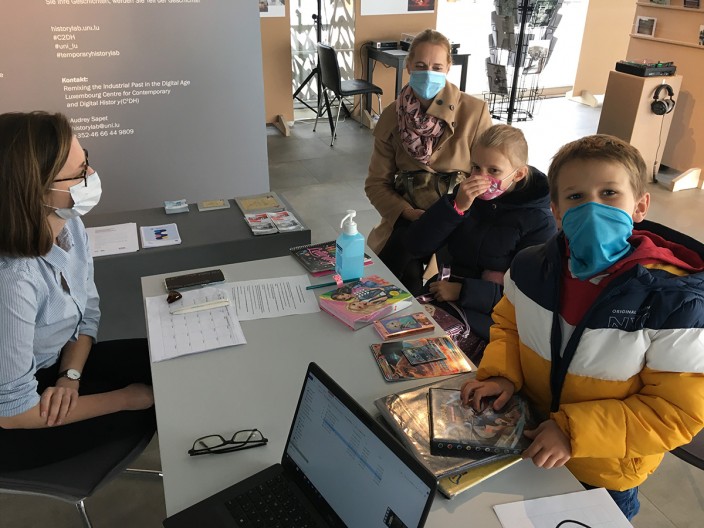

From 26 September to 23 October 2020, we ran such a history workshop (we called it a “temporary history lab”) in the Annexe22 pavilion, a small exhibition space on one of the two main squares in Esch-sur-Alzette.1 One of the team’s2 most formative experiences during the four weeks the public lab was open was the daily contacts with visitors. Most of the team members were brought into the research project because of their academic qualifications, as measured by the quality and number of their scholarly publications, presentations, awards and other “academic capital”. In the Temporary History Lab, they now had to become public historians. They all had to realise that, in practice, public history as a citizen science of the past requires both good preparation and the sharpening of one’s own perception and communication skills to deal with visitors from a non-academic environment. The specific challenges raised by the Temporary History Lab included actively and informally approaching people in the pedestrian area in front of Annexe22, putting aside one’s own inhibitions and reservations, extending personal invitations to talk in the pavilion, using events such as the Escher Family Day on 26 September 2020 to make contacts, and presenting the project to visitors in a generally understandable way. In direct conversation, it was important to quickly adjust to different mentalities, life experiences and cultural backgrounds, to listen attentively, to ask empathetic and understandable questions about topics relevant to the research, to follow up, and to carefully document content and further contacts.

In the discussions with the visitors, the existing language skills of our international team proved to be an indispensable prerequisite for success, because although the majority of the visitors spoke either German or French, quite a few of our guests felt much more comfortable in Luxembourgish. As a Luxembourger, Daniel Richter was an often sought-after team member for these “home games”. The proportion of Italian, Spanish or Portuguese speakers in the History Lab was unfortunately rather low. However, individual team members also used these languages confidently when necessary.

Practising public history in times of COVID-19

A particular challenge of the daily work in the laboratory was dealing with the acute COVID-19 situation. What were the consequences of the restrictions governing contacts, the distancing requirements and the hygiene regulations on activities in the pavilion? What impact did the restrictions have on the team’s goals for the laboratory?

The COVID-19 pandemic had already affected the team’s preliminary work in the months leading up to the opening of the Temporary History Lab and had a significant impact on the planning of the programme. The school workshops with primary school classes planned for spring 2020 had to be postponed at first and then dropped from our list of activities. This also applied to lecture events and visits to the pavilion by larger groups, e.g. groups from local retirement homes. The implementation of other participatory activities, such as those planned with the residents of the Brill neighbourhood, was out of the question under the prevailing pandemic conditions.

- 1. The goals of the History Lab were the presentation of the project to the public, the collection and digitisation of research data, further networking for the research project in the region, and the production and practical application of public history tools.

- 2. Team members: Stefan Krebs (PI), Maxime Derian, Viktoria Boretska, Daniel Richter, Irene Portas, Julia Harnoncourt, Jens van der Maele (all researchers), Lars Schoenfelder (designer), Werner Tschacher (coordinator).

The number of visitors to the pavilion was subject to a quantitative restriction: no more than three team members and six visitors were allowed in at any one time. Direct communication between researchers and visitors only took place in specific contexts: to deal with ongoing visitor traffic, at individual events and for the submission of historical documents and photos for digitisation. The collection of metadata and background information about sources, an essential task for crowdsourcing, was able to take place smoothly. However, the requirement to wear masks inhibited direct communication in the pavilion, as interested parties often could not or did not want to stay for longer periods. In-depth oral history interviews could not take place in the pavilion under these conditions; only shorter one-on-one conversations and the exchange of contact information were possible. Nevertheless, there were impressive conversations and lasting contacts were made with contemporary witnesses and their descendants, who reported on their lives in Esch and the Minett region, touching on topics such as persecution during the Nazi occupation, work in industry and administration, childhood and family, living conditions, environmental problems such as dust, odor and noise pollution from industry, regional rail traffic and the significance of the border and immigration.

Proximity and distance in interplay

The interplay of real and perceived proximity and distance as determined by the pandemic also came into focus – whether directly or indirectly, intentionally or unintentionally – in the various participatory activities in the History Lab. Which aspects were affected, and how can the team’s perceptions and practical experiences be transferred on a meta-level into insights into the practice of public history?

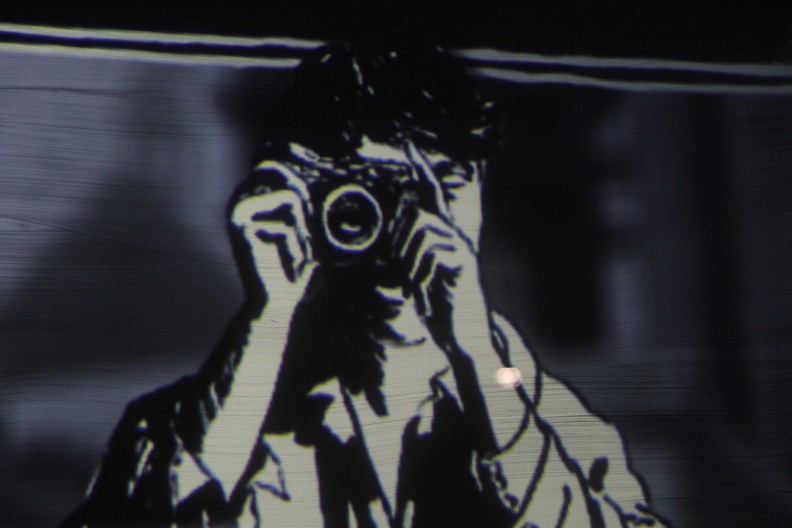

The exhibition on portrait photography organised by Viktoria Boretska and Lars Schoenfelder was particularly conducive to further reflections on proximity and distance, as it focused on the relationship of photographers with their subjects in their industrial working environment. The exhibition was shown to visitors during the first week of the History Lab. It demonstrated that over the course of the 20th century, photographers increasingly reduced their spatial and social distance from the subjects they photographed.

The photographer’s camera was getting closer, gradually entering private lives and pointing at everyday objects and practices, giving them attention and value.

Exhibition text/Viktoria Boretska

In industrial photography, the formerly impressively staged industrial environment was increasingly reduced and people themselves became the focus. The ultimate expression of this trend was the action self-portrait used by the Dudelange Photo Club in 1981, which united photographer and subject in one person, called authorship into question and thus created a very peculiar combination of proximity and distance. A parallel development took place during this period in the historical sciences, with a shift in research interest away from large-scale social-historical structures towards the micro-level of everyday human life and cultural-historical themes. The life stories of ordinary people competed with those of the great figures of more traditional historiography. The role of historians as the sole authors of history was also called into question, paving the way for the emergence of increasingly participatory and multi-perspective history projects and subsequently for a greater acceptance of public history within historical scholarship.

The exhibition was complemented by a self-portrait event running in parallel to the exhibition, in which an analogue camera with a cable release was used. The use of a digital camera was deliberately avoided so as to give visitors their very own self-experience via the detour of the analogue medium, by placing them on the chair provided in front of a white wall and making them press the shutter release of the camera set up at some distance, and to question present-day selfie practices. By also photographing smaller groups of visitors and families, it was possible to create proximity and intimacy on the one hand, while on the other also creating a temporal distance by the fact that those photographed could not pick up their own portrait photos and see themselves in the role of the photographic subject until the last days of the lab, two weeks later. By opting for this temporal distance from the active event of photographing themselves, the team inserted the perception of alienation as a stylistic device into the process. The self-portrait event and exhibition about industrial photography thus provided a certain counterpoint to the distance dictated by the acute pandemic situation.

The setup of the installation and the remote shutter release were essential for the self-portrait event, as people could choose the exact moment they wanted to be photographed. Additionally, the analogue camera helped to create a kind of distance between the people and the technical process of photography. Without the ability to review and see the images immediately, the one image that could be taken continues to gain value.

Lars Schoenfelder

Creating proximity despite distance

The most spectacular part of the Temporary History Lab was probably the interactive video installation that the researchers developed together with the video artist Chiara Ligi and the Milan based artist collective Tokonoma.

The artists, musicians, and animators behind scenography team Tokonoma have been a pleasure to work with: they were precise, quick, and, above all, inspirational. During the process of creating an exhibition, scenographers sometimes require a lot of detailed ‘input’ from the historical research team; Tokonoma, in contrast, effectively ‘thinks ahead’ of the researchers – and as such, they have come up with various wonderful ideas we could never have conceived ourselves.

Jens van de Maele

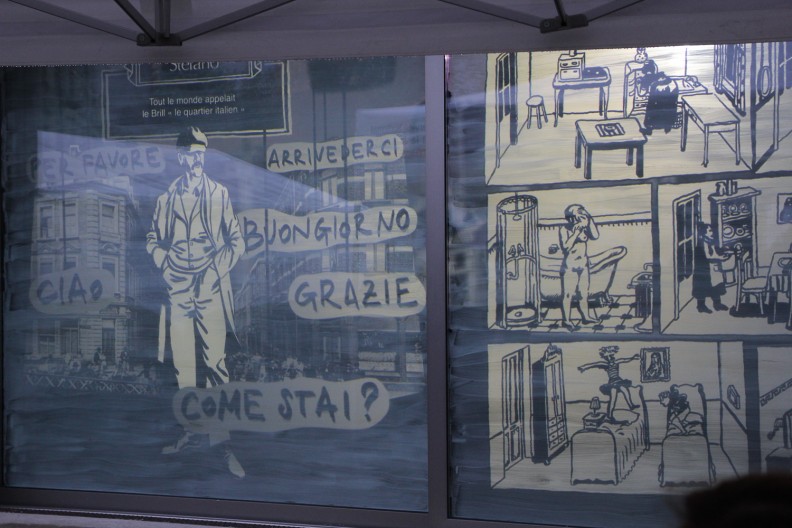

The original concept for the video installation had to be modified due to the uncertain pandemic situation, which enforced a general adherence to distancing rules among visitors. The pre-COVID plan was for visitors themselves to contribute historical documents to the video installation through crowdsourcing. In addition, direct interactions and conversations with visitors would have taken place during public events on the forecourt and inside the pavilion. After extensive deliberation, the team decided to change these plans and to project a video installation onto the main windows of the pavilion so that visitors could watch the videos from outside. While this ensured the physical distance required because of the pandemic, the team developed several ideas to create a kind of distant intimacy for communicating our research findings to a wide audience: 1) We chose stories that addressed basic human needs and difficulties to make it easier for the audience to identify with historical people and subjects; 2) We chose spoken personal life stories from a first-person perspective to create a psychological proximity between audience and historical protagonists; 3) Tokonoma’s audiovisual dramatisation (drawings, animations and soundscape) of the historical content aimed to elicit an emotional reaction from the audience. The storytelling and staging helped the visitors to identify with the historical characters.1

Each of the six figures represented one of the many untold stories from the region.

Putting together a character that was as representative as possible from the memories and traces left over from people’s everyday actions made it clear how many untold stories and perspectives still lie dormant in the Minett, which will hopefully get the attention they deserve in the future.

Daniel Richter

The narrative concept of telling first-person life stories confronted the team with the problem that the life stories of “ordinary” people are often very difficult to retrieve from archival sources. We therefore also decided to create some composite historical figures that were built on biographical fragments from different yet similar historical people. The chosen ensemble of characters can be divided into three groups:

- historical figures: Yvonne Useldinger and Léon Molitor

- semi-historical figures, in which biographical elements of several historical people were combined in the absence of one comprehensive biography: Giraldo and Stefano

- historical ideal types embodying the main characteristics of a particular group of people: Tony and Anna

The most emotionally charged character was undoubtedly the historical figure of communist and women’s activist Yvonne Useldinger (1921-2009), whose deportation to the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp represented wartime suffering under the Nazi occupation of Luxembourg.

- 1. The projection from inside the pavilion onto the two side windows facing the park used modern computer and sensor technology to animate six personal short stories and thus highlight different aspects of the history of the Minett region. The characters animated in the video sequences, their spoken texts and the superimposed historical documents were the result of intensive archival research and close creative and editorial collaboration between various working groups in the team.

Yvonne Useldinger, who was part of the resistance against the NS regime, impressed me a lot with her courage and it seems as if it was inevitable for her to resist, without her maybe even realising the uniqueness of her effort. Out of our respect for this historical person, we decided to produce the text as closely as possible to her own words, extracting it out of her interview, a very rewarding task.

Julia Harnoncourt

In another video sequence, the physician Léon Molitor (1901-1979) criticises the problem of air pollution caused by industry in the region around Esch, still vividly remembered by the older inhabitants of the southern region.

The two semi-historical characters introduced visitors to the history of industrialisation and deindustrialisation of the Minett region. Extensive use was made of historical documents, which were incorporated into the animations as digital copies to enhance the effect of historical “accuracy”.

Giraldo Strinati is a composite figure developed from real elements taken from oral history interviews supplemented by archival information on the technical tools and facilities used by miners. This fictional but very realistic character is a retired former miner, aged about 80, who in 1982 talks about his experience at the mine from 1920 to 1967. Much of the speech, taken from the testimonies of miners, reflects the ambivalence of the perception and specificity of life in the mines at the time.

Maxime Derian

A similarly composed character vividly portrayed the story of migrant workers and their housing situation in the south of Luxembourg: Stefano, the son of an Italian miner, grew up in Esch from 1931. He later became a painter in the Brill district of Esch.

The historiographical bricolage of Giraldo and Stefano is reminiscent of Alain Corbin’s reconstruction of the largely unknown life of the northern French clog maker Louis-François Pinagot (1798-1876)1 – a biography of what is possible between the realistic closeness generated by the historian’s work on the one hand and the distance caused by the man’s disappearance from all memory on the other, which can only be bridged by plausible fiction.

As a historical ideal type, the historian Anna was representing our own intentions as public historians with the Temporary History Lab: to meet contemporary witnesses from the Minett region, to exchange with visitors and to invite them to investigate the industrial history of the region together with us.

- 1. Alain Corbin, Le monde retrouvé de Louis-François Pinagot, Paris 1998.

The historical ideal type of the young photographer Tony embodied the personal experience of the economic and cultural transformation of the Minett region through the decline of industry in the 1980s. The video installation brought this to life as the experience of an entire generation.

A collective character, like Tony, meant to express the spirit of the new generation of photographers, the ‘young wolves’: They didn’t want to follow the rules or rewards, promoted photography as art and said it belonged to everyone. Trying to imagine talking like this young cool guy from the 1980s, although not travelling back through centuries, was still quite Orlando-esque!

Viktoria Boretska

Conclusion

In retrospect, the Temporary History Lab can be seen as a site of hybrid historical mediation. It was a place of learning about public history, a place of growing self-awareness for the research team, whose members had to overcome their own aloofness because of COVID-19 (no one would have predicted a pandemic, of all things!) in order to actively approach people from the non-academic public. Visitors were confronted with a combination of unusual analogue and modern digital offerings that created an interplay of proximity and distance. Given the circumstances, the Temporary History Lab could not produce history in the sense of sharing authority. Learning and research through discovery was hardly possible inside the lab because of the COVID-19 situation. Some of the mediation activities were based on traditional approaches and, like the self-portrait activity, set a counterpoint to the digital world and modern media use. The interactive video installation allowed limited activation but no real participation from the visitors. They were not involved, or at the very least only indirectly, in the production of the video sequences, which they could access as viewers. The primary aim of the characters was to evoke emotional responses from visitors. With over 300 individual uses, the video installation nevertheless proved to be a well-functioning medium for conveying history.

Against all odds, public history has helped to build bridges between historical scholarship and residents of Esch and the Minett region. Perhaps the hybrid Temporary History Lab in times of COVID-19 can give us a hint of the needs and contours of a post-pandemic public history, situated somewhere between proximity and distance.

Image credits: Lars Schoenfelder (photos, video), Noëlle Schon, Daniel Richter, Werner Tschacher (photos)