Strolling around the town of Esch

Anyone who checks out Esch-sur-Alzette on Google Maps is led to believe that the town’s namesake – the Alzette river, or Uelzecht in Luxembourgish – flows openly through the town centre. In reality, however, the Alzette is completely covered for most of its trajectory through Esch and, for present-day visitors, the only indication of the river’s existence can be found in the name of the town’s main street. Buried under the rue de l’Alzette/ Uelzechtstrooss, the Alzette has now given way to another kind of stream – the one created by the coming and going of people visiting Luxembourg’s longest pedestrian shopping street. The river flowing under the city is just one of the testaments to radical transformation of the natural environment during the industrial age of Luxembourg’s South, prompted by the discovery and subsequent exploitation of iron ore from the 1850s onwards. The centre of Esch, explored by the REMIX team on a cold November day, reflects its past great wealth, generated and accumulated during a time of rapid industrial growth.

Notwithstanding a few modernist additions from the last post-war era, the rue de l’Alzette is still characterised by a large number of stately town houses constructed during the belle époque. Despite its fairly small size, Esch effectively boasts a remarkable variety of architectural styles – from rational 1930s neoclassicism (e.g. the Town Hall) and turn-of-the century neo-Renaissance (e.g. the Lycée de garçons) to Art Nouveau-inspired eclecticism. A prime example of the latter style is the so-called Meder-Haus (nowadays the Centre de rencontre et d’information pour jeunes), whose 1907 design is a near-perfect copy of a pre-existing Parisian town house. As such, the Meder-Haus illustrates how Esch’s early-20th-century bourgeoisie eagerly emulated the aesthetic modes and conventions developed in neighbouring countries. Amidst these architectural remnants, we also noticed many signs of more recent flows of ideas and people, including a number of street benches bearing public messages in Portuguese.

Moving further on and away from the centre, we discovered the residential area of former maisons ouvrières. The rows of workers’ housing, homogeneous and quite unlike the stylistically diverse buildings in the centre, comprise tiny houses, each with a total surface area of 45m2, painting a picture of what the workers’ everyday lives may have been like and which spaces they were associated with. Although it now shapes the suburban landscape of the town, such housing was only available for qualified workers at the time. Unqualified workers were often confined in overcrowded buildings, where they endured unhygienic conditions and were exposed to health risks (e.g. tuberculosis). These examples indicate that ARBED, the largest iron and steel manufacturer in Luxembourg (founded in 1911), was and still is metaphorically referred to as a “state in a state”, devising its own regulations and crafting its own vision of welfare for its workers.

Setting foot in the steel plants

During our tour, we were introduced to several heritage workers striving to protect, preserve, and to breathe new life into the industrial past of Luxembourg’s South. The first was Henri Clemens, a leading figure in industrial heritage protection in the region, whose lively speech revealed his eagerness to give a new purpose to buildings previously dedicated to the production of iron and steel. Henri, co-founder of the Entente Mine Cockerill, shared with us how preserving traces of the contemporary industrial past entails a plethora of struggles, as the steel industry does not fall within the category of “cultural heritage” from a conventional viewpoint. He guided us through the rue des Artisans, a series of buildings once serving the maintenance of the ARBED Terres Rouges plant, from where we had a view of the slag heap left over from the time of industrial production.

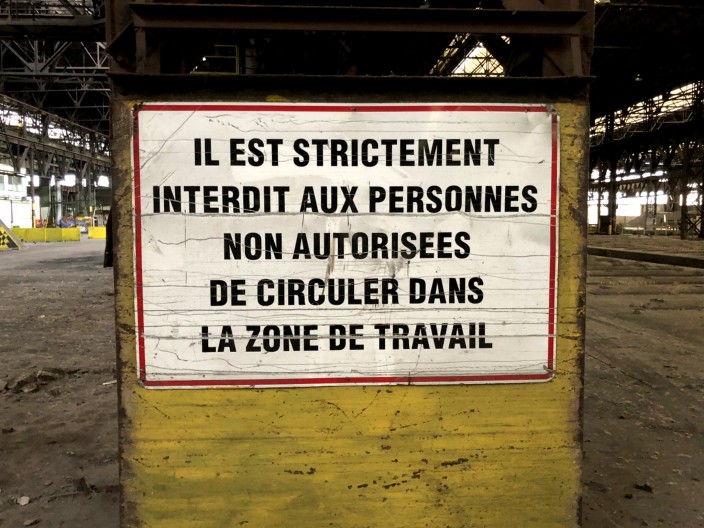

After our lunch break, we continued our visit by heading to the impressive industrial conglomerate of Esch-Schifflange. This site was temporarily closed in October 2011 and had terminated its activities altogether by the end of 2014. During our visit, we could actually witness the ongoing demolition of the remaining sites. There are plans to turn the decaying factory into a residential area, transforming certain industrial buildings to accommodate public services for future inhabitants. Accessing this abandoned industrial site was made possible by Alain Guenther and Victor Merens, members of the Amicale Schëfflenger Schmelzaarbechter association. As passionate collectors, they are pursuing the cause of preserving the industrial heritage of the “Minette” region. They founded a museum about the site, De Schmelzaarbechter, which was officially inaugurated in 2015 and whose collection will serve as important source for the REMIX project.

During our visit, Alain and Victor provided us with insightful explanations about the various functions of each building, with detailed yet accessible information about the steelmaking process. Their words brought to life an abandoned past as we navigated the vast compound. The past was transposed to the present through objects carelessly left behind when the plant closed down. Items including newspapers, chairs and sketches of industrial processes all created the impression of a time void, alienating us from what was a daily reality for thousands of workers. Built in 1871, the plant experienced both growth and decay over 140 years. At the same time, the site gave us a glimpse of the colossal architecture needed to manufacture (semi) finished steel products. These vast spaces and fragments of remembered past can be filled with the (hi)stories that REMIX team members will work on over the course of the project.

Exploring uniqueness in the commonplace

The age of industry dramatically transformed countless places around the globe, many of them coming to bear a striking resemblance to one another. Indeed, the age of steel prompted the emergence of a global steel network and ‘society’ with similar processes, policies and practices. Luxembourg’s South and the town of Esch undeniably reflect global patterns of industrial development, but they also contribute to and diversify them because of the unique nature of the region. On the border between Luxembourg and France, Esch-sur-Alzette is a place that has defied – and continues to defy – clear-cut interpretations of local and national identity. Not unlike the country of Luxembourg itself, Esch can be considered a microcosm determined by multiple and regularly shifting identities. Attracting a workforce from way beyond Luxembourg’s borders, the steelmakers’ metropolis was transformed into a town of immigrants, whose presence would define not only the urban landscape (e.g. through the construction of labourers’ quarters) but also the local culture. In Esch, the typical problems associated with rapid industrialisation and the more recent de-industrialisation, such as poverty and urban decay, have always existed alongside more positive phenomena, such as a relative openness to newcomers and a willingness to repeatedly reinvent itself as a community. This distinctively and deliciously complex setting is the unique site of research for our REMIX project, which aims to (re)introduce the town to the local, national and international public when it becomes European Capital of Culture in 2022.