Time is scarce

The Papalagi never has enough time. He has even divided the day up, like we cut up a coconut. And all the parts have a name: seconds, minutes, hours. I’ve never been able to understand this system, and anyway there’s no point thinking about such infantile things. When one of their time machines sounds, he says: “Oh no, an hour has already gone by.” I don’t really understand this obsession, I think it’s a serious illness. There are Papalagi who say they never have time, and they run around as if they were possessed by the devil. They don’t realise that the time is there if they want it.

This observation supposedly comes from a Samoan chief who visited Europe in the 1920s and commented on the hectic lifestyle of its inhabitants. But it’s a hoax.

German artist and author Erich Scheurmann did visit Samoa, but he turned his own romanticised insights about the “noble savages of Samoa” into speeches by the fictitious chief Tuiavii. This fraudulent Samoan perspective on the Western lifestyle does have a certain appeal for us, however, in that it is applicable to our own biotope: the university.

As Maggie Berg and Barbara Seeger have convincingly argued in their book ’The Slow Professor’, academic life is increasingly characterised by fragmentation and distractedness caused by the pressure to write applications, to publish, to integrate new administration systems into our workflow, to attend to students and courses, to review papers, to visit, present and organise conferences, lectures and workshops, and to constantly update and quantify these activities.

The email avalanche

All these tasks generate a daily avalanche of emails that have to be answered and are particularly burdensome for heads of department who don’t have the time to properly address all the issues raised. Their coping strategies vary from never answering emails, or only answering them when there is a direct imminent interest, to dealing with some of the issues raised in the email in a short and snappy style. The latter is the friendliest approach but threads of uncertainty persist and issues bounce back onto the agenda again and again. The consequence of these dynamics is that small issues remain unresolved and there is relatively little space for engaging in new initiatives that come on top of core activities. How can colleagues find the time to explore a new teaching resource when they don’t even have the time to properly answer their emails? I understand that it’s not a question of being uncollegial or uninterested; it’s about being selective in order to survive and not become completely snowed under with work. But how did we deal with these issues before the introduction of email?

The curriculum as safehouse or fortress

It is no wonder that established curricula can sometimes take the form of safe houses, contexts in which lecturers feel confident and want to stay in charge. They are the “agents”, drawing on “ingrained practices” in which they have struck a balance between personality, research interests and teaching skills. Determining the content and form of their teaching appears to be part of their professional identity. Imposing innovation in their day-to-day teaching practice may have the effect of turning the safe house into an impregnable fortress – a space where they are in command and refuse any interference. So what is the best way to deal with this context when you are not in charge of teaching, you are on a temporary contract and you are looking for an audience for your carefully crafted teaching resource on digital source criticism at your own University? How did I see the adoption of my teaching resource working out in practice?

Assumptions on the uptake of teaching material from Ranke.2

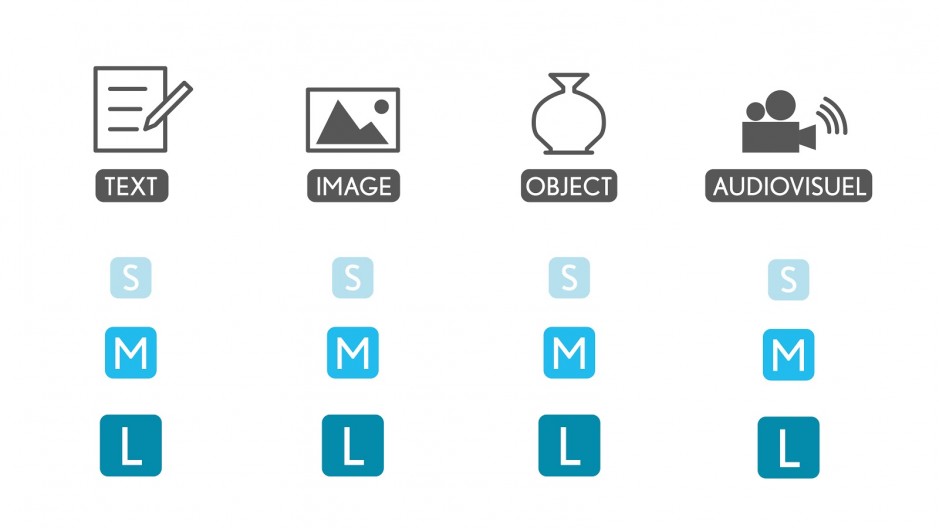

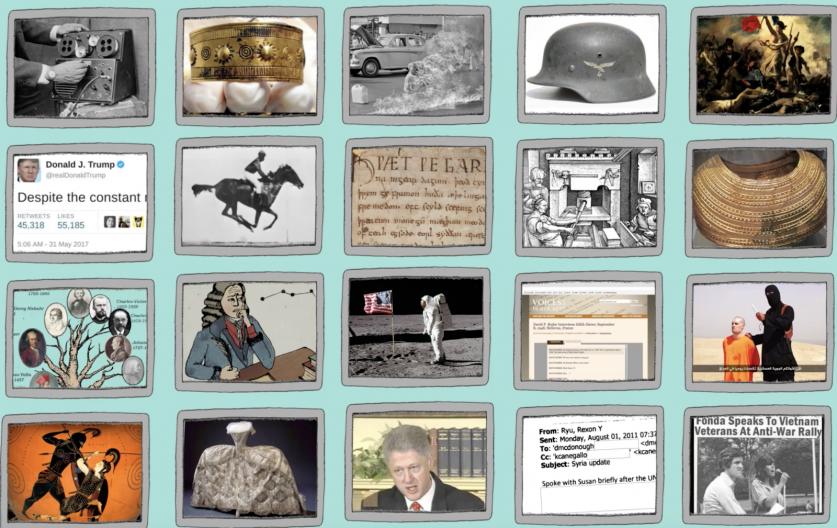

The concept of Ranke.2, a teaching platform with lessons on digital source criticism, is based on offering content to lecturers and students that can be adapted to suit varying levels of digital capability and differences in available time. This choice was made on the basis of feedback from colleagues who kindly participated in a number of focus groups during the development phase of Ranke.2. We therefore chose to create lessons that consist of independent modules: the SMALL module is a very short track consisting of an animation and a quiz; if lecturers have more time, the MEDIUM option offers a variety of assignments and an answer template; and if the objective is to provide students with a real hands-on experience, the LARGE module includes a tutorial for a workshop. The reasoning was that no lecturer would refuse the offer of a resource that teaches students what digital source criticism is in a nutshell, takes only 20 minutes of their time, with no need to register or download data or tools, and with the possibility to tweak the teaching material to their own preferences. But notwithstanding the enthusiastic reception, I now realise that I still do not have a full picture of how communication with and persuasion of my peers works. There seems to be a crucial difference between lecturers who have already identified “a need” for my resource and embraced the paradigm of “digital history”, and those who are yet to – and may never – do so.

Method or narrative - where does Ranke.2 fit in?

Last Tuesday I held a meeting with colleagues of which I know that they will be teaching history courses in 2019. One of them, the very first to use the material from Ranke.2, managed to tweak it for her own purposes and was willing to explain how she had used it in her class. My naive expectation was that after her presentation, the others would outline the lessons they had planned and we could brainstorm about how to integrate elements of Ranke.2. We were however immediately confronted with differing opinions on the suitability of discussing digital source criticism in regular history courses. What is the place of Ranke.2 in a series of lectures about the history of Europe and European integration for 150 students from different humanities disciplines? The objective of this course is to get students to carefully listen to the lectures and read the literature, to reflect on the content in such a way that they are able to identify generic concepts and processes from specific historical narratives, and to apply them to other contexts. Why should this very important academic training make room for an animation and quiz about source criticism? The answer from the colleague who had already used Ranke.2 material in her class was that she feels that knowing about the origins of sources is relevant for any teaching activity related to history. Does this imply that because of the digital turn, we now have to upgrade the relevance of “source criticism” and include it in every single teaching context? How realistic is that? I realised that in my fervour to publicise my “digital darling” Ranke.2 , in which we had invested so much time and effort, I forgot that its relevance is a question of policy and choices that need to be made with regard to the overall design of the curriculum. How can we strike a balance between understanding abstract concepts and processes and acquiring basic knowledge about how digitisation and search engines work, within the constraint of the fixed number of hours in a course?

We need to talk, print and sit around a table

The assumption of the creators of Ranke.2 was that the appearance of the website would immediately catch the attention of our target group. So I was a little disappointed by some feedback I received about how a colleague who teaches on research methods felt so overwhelmed by its appearance that he decided not to use it. Although I had put a good deal of effort into creating easily digestible small units of information, his impression was that he could only engage with a lesson in its entirety. When I expressed my surprise about this reaction, the colleague who had worked with Ranke.2 pointed to my blind spot:

“The reason I took the effort to read the introduction and sift out what I could use for my lesson is because I already knew it was in there! I know you, you taught a hands-on lesson in my course about finding sources online, I saw how the handout worked with the students and could repeat the process with what I found on Ranke.2.”

She then distributed the printed handout among her colleagues and the effect was amazing. Only then could they actually envision how the answer template could be used in practice in their lessons. They recognised the tables with categories and the questions – they were similar to what they had tried to do themselves. Ranke.2 entered the mental box of recognisable practices when the lecturers talked to each other, instead of attending one of my presentations on the concept of Ranke.2, and when they looked at a printed handout of an assignment, instead of browsing through the website with no clue what to expect. One could argue that it’s all in there – you just have to read the introduction! This is true, but just as we have a strange aversion to following the logical sequence of texts in a museum or browsing through the FAQ when we have issues with an online service, we are reluctant to read and browse through the tabs of a website without having a vague idea about how much time it will take to find something we need. We prefer the mediation of a human being who can lead us straight to the relevant item. This insight led me to consider a shift in strategy: 1. Instead of convening meetings, I should invest time in giving guest lectures during my fellow colleagues’ courses, and 2. The downloadable and tweakable answer templates and handouts that can be used in any lesson should be more visible on the website. I am grateful to my “informed” colleague, who made me realise that I have to be patient and focus on lecturers who have already identified a need that Ranke.2 can satisfy. There are plenty of them!!!