Germany’s invasion of Luxembourg on 10 May 1940 brought about a major doctrinal shift in the country’s foreign policy. The government, in exile in London and North America until September 1944, abandoned the policy of permanent, unarmed neutrality that had been introduced by the Treaty of London in 1867. Joseph Bech, Foreign Minister since 1926, who had been committed to observing Luxembourg’s neutral status to the letter, informed Prime Minister Pierre Dupong that this policy would no longer apply in a letter sent in January 1941.1 In late August 1942, the Nazi occupiers suppressed resistance movements among the Luxembourg population against the introduction of forced conscription of young Luxembourgers into the German army. Hugues le Gallais,2 Minister Plenipotentiary of Luxembourg in Washington, sent a letter to the US Secretary of State Cordell Hull on 8 September 1942 in which he emphasised that in view of events Luxembourg considered itself to be at war against the Axis powers.3

This paradigm shift in the history of Luxembourg diplomacy, imposed by the force of events, was not without consequences for the development of Luxembourg’s diplomatic corps and activities after the Second World War. Luxembourg became a founder member of all the major international organisations established after the conflict: the United Nations (UN) in 1945, the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC)4 in 1948, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and the Council of Europe in 1949, the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951, and the Benelux, a customs union between Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, founded by means of an agreement signed in London in 1944 by the three governments in exile which came into force on 1 January 1948. It was clear that Luxembourg needed a professional diplomatic corps capable of informing, advising and representing the government in these organisations and in the new friendly and allied countries.5 The Act on the Organisation of the Diplomatic Corps was adopted by the Chamber of Deputies on 11 June 1947.6 The Act stipulated that “the diplomatic staff includes, in hierarchical order, the following officials: Envoys Extraordinary and Ministers Plenipotentiary, Legation Counsellors, Legation Secretaries, Legation Attachés”.7 The next step was to find men to carry out the tasks assigned to the new diplomatic corps (no women were recruited as diplomats before the 1970s).

It is difficult to trace the history of the Luxembourg Ministry of Foreign Affairs, even today. The only documents available for consultation in the Luxembourg National Archives are those produced by the Ministry up to 1973. It appears that the new Archives Act8 alone will not facilitate access. For this reason, the use of other sources like oral testimonies is essential. As well as filling the gaps in written sources that may be missing or inaccessible, oral sources shed light on both the individual and the collective, while also highlighting the networks in which the interviewed diplomats were involved throughout their lifetime.9

- 1. Linden, André. Luxemburgs Exilregierung und die Entdeckung des Demokratiebegriffs. Mersch, Luxembourg: Capybarabooks, Éditions Forum, 2021.

- 2. Schmit, Paul. Un diplomate luxembourgeois hors pair: L’ambassadeur Hugues Le Gallais dans la tourmente de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Luxembourg: Saint-Paul, 2019.

- 3. Kayser, Steve: La neutralité du Luxembourg de 1918 à 1945, in Forum 257, 2006, pp. 36-39.

- 4. Formed to administer Marshall Plan aid for the reconstruction of Europe.

- 5. Schroeder, Corinne: Le corps diplomatique du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, in: Dumoulin, Michel, Lanneau, Catherine (eds): La biographie individuelle et collective dans le champ des relations internationales, P.I.E. Peter Lang, Brussels, 2016, pp. 177-193.

- 6. Act of 30 June 1947 on the Organisation of the Diplomatic Corps. Legilux https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/1947/06/30/n1/jo

- 7. There were no ambassadors at that stage; the position would only be created in 1955.

- 8. Act of 17 August 2018 on Archiving.

- 9. Fridenson, Patrick, in Descamps, Florence: Archiver la mémoire. De l’histoire orale au patrimoine immatériel. Editions de l’école des hautes études en sciences sociales, 2019, pp. 9-23.

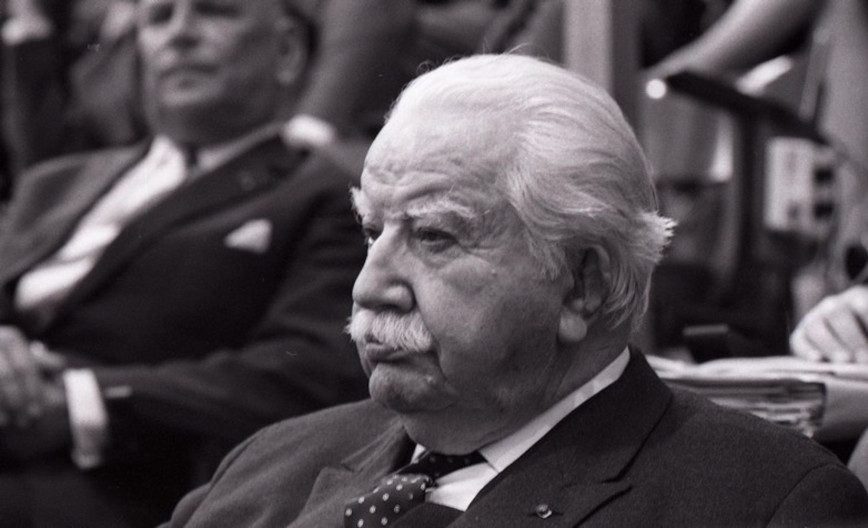

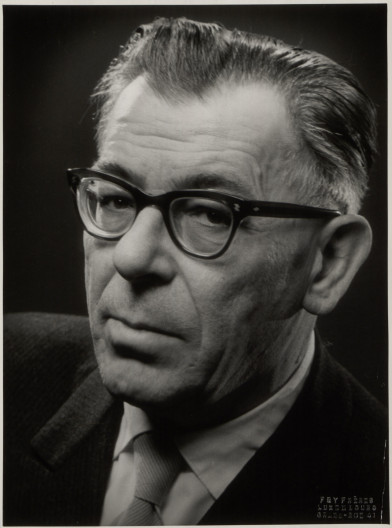

A first series of interviews was recorded from 2008 to 2010 by the Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l’Europe (CVCE) with some of Luxembourg’s first career diplomats, appointed in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Seven interviews (six filmed and one audio recorded) carried out over this period have been published in full and as a series of themed excerpts on the website www.cvce.eu. The interviews cover political topics such as Luxembourg’s integration into the various European and international organisations and its bilateral relations with countries in which it had a diplomatic representation. These diplomats, all of whom started out under the authority of Joseph Bech,1 discuss the development of Luxembourg’s diplomatic apparatus. They touch on the challenges associated with the opening of new embassies, the resources allocated to diplomats to carry out their missions, the development of administrative structures in the Foreign Ministry and the relationships between diplomats and their respective ministers. In total, more than 27 hours of recordings are freely accessible on the website www.cvce.eu, in full or divided into themed excerpts and accompanied by transcripts.

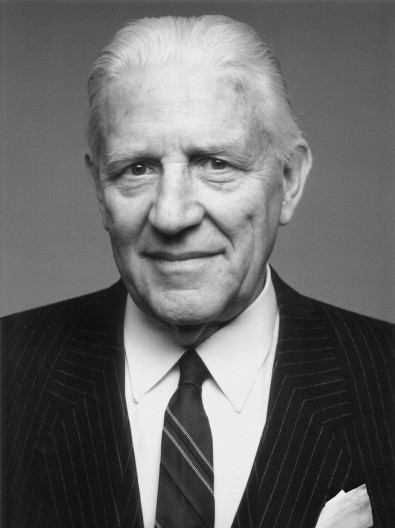

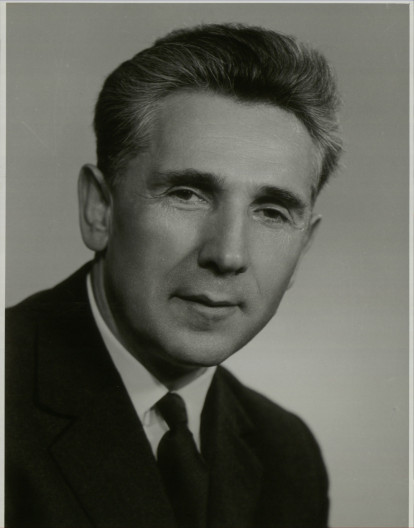

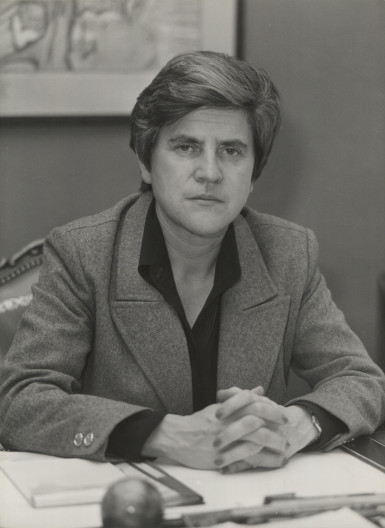

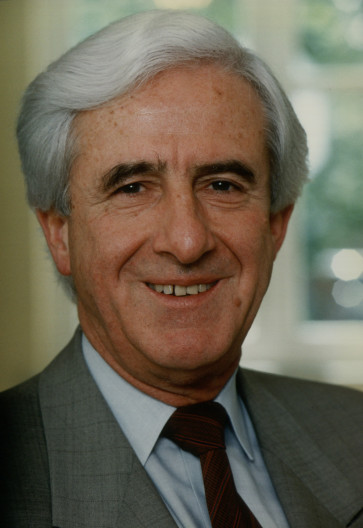

A second series of interviews was conducted with a new generation of ambassadors between 2020 and 2022 by the C²DH, again with the support of the Luxembourg Ministry of Foreign Affairs. These diplomats, all of whom retired between 2005 and 2017, speak about the development of the structures and organisation in the Ministry as well as the new priorities for Luxembourg diplomacy. They describe how the diplomatic service set out to develop relations with new economic partners all over the world, in particular on the initiative of Gaston Thorn,2 Foreign Minister from 1969 to 1980. The manifold efforts by the national diplomatic service in the area of economic development and the first steps in what would become the current policy of nation branding are presented. The diplomats also share their memories of two major pillars of external action within Luxembourg foreign policy over the past 40 years: European integration (especially the Luxembourg Presidencies of the Council of the European Communities) and the policy of cooperation and development aid for third countries, particularly in Africa and South-East Asia. The accounts describe the role of diplomats in responding to the international criticism levelled at the financial centre from the 1980s onwards. Finally, this second series of interviews also sheds light on developments in Luxembourg diplomacy after the geopolitical upheavals that began in 1989 (the fall of the Berlin Wall, German reunification, the collapse of the USSR, etc.).

These six new interviews, all filmed and representing a total of 30 hours of footage, will be published on the website www.cvce.eu.

- 1. Joseph Bech was Luxembourg’s Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1926 to 1958. He also served as Prime Minister from 1926 to 1937 and from 1953 to 1958.

- 2. Trausch, Gilbert: The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Grand-Duchy, in Steiner, Zara (ed.): The Times Survey of Foreign Ministries of the World, 1982, pp. 345-361.